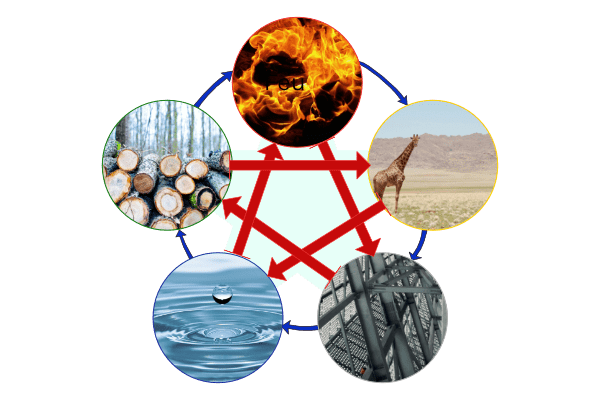

Emotions therefore play a major role in the development of stagnation. Depending on the emotion involved, it will manifest in the organ to which it is connected.

Thus, excessive joy—or excitement—leads to stagnation of qi in the heart. The heart may begin to beat irregularly or too rapidly. This can also lead to hypertension, insomnia, a restless mind, etc.

Anger leads to stagnation of Liver qi, the main organ responsible for the free flow of qi throughout the body. This can lead to vision problems, diarrhea, dry and brittle nails, tinnitus, dizziness, and headaches. This stagnation—or overpressure of Liver qi—is also the cause of premenstrual syndrome or depression. According to the Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine, pain in the body is a direct result of anger interfering with the flow of Qi in the Liver.

Persistent thoughts or mental rumination can lead to stagnation of Qi in the Spleen and a loss of its vitality. This can result in decreased appetite, bloating, mental fog, and an inability to solve problems.

To remedy this, it is therefore important to be aware of our emotions, to be conscious of them, and not to let them control us. By cultivating a calm mind daily, we can limit the risk of emotional outbursts and, consequently, stagnation.