Huang Di: The Yellow Emperor

The father of Chinese Medicine

The Yellow Emperor, Huang Di (黃帝), occupies a unique place in the Chinese imagination and collective memory. He is also a key figure in the origins of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). Indeed, tradition attributes to him the authorship of the Huangdi Neijing (黃帝內經, The Inner Canon of the Yellow Emperor), the foundational text of TCM.

A semi-legendary figure, he is believed to have been born in the 27th century BCE and to have reigned for approximately a century. More than just a sovereign, he represents a sage, an inventor, and a spiritual guide. His virtues make him a role model in many respects and an inspiring figure.

A civilizing hero

According to ancient chronicles, such as the Shiji of Sima Qian (1st century BCE), Huang Di was born in the Youxiong Plain under the name Xuanyuan (軒轅). From a young age, he distinguished himself by his extraordinary intelligence, insatiable curiosity, and innate sense of governance.

His reign is associated with the settlement of populations, the establishment of stable political structures, and numerous inventions. Traditions attribute to him, in particular, the institution of the calendar, the domestication of animals, the use of boats, the introduction of ritual music, and the invention of writing, thanks to his minister Cang Jie.

Thus, Huang Di is not only a political leader but also a civilizing hero. He is said to have “united the scattered tribes under one sky” and that “through his virtue, he fostered harmony among humankind.”

The contribution to Chinese medicine

Huang Di is considered the author—or the inspiration—of the Huangdi Neijing (黃帝內經, Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic), a work that remains a key reference for contemporary Chinese medicine. Although it is unlikely that he actually wrote this text, tradition attributes its authorship to him, a testament to the moral and intellectual authority he held.

The Neijing takes the form of dialogues between Huang Di, the Yellow Emperor, and his physician, Qi Bo. The emperor asks questions, the physician answers; together, they explore the nature of the human body, the causes of illness, and methods of prevention.

The text (see box) lays the foundations of Chinese medical thought: the balance between Yin and Yang, the circulation of Qi (vital energy), the role of the five elements (wood, fire, earth, metal, water), and the intimate connection between humankind and nature: “Humankind is born from the Earth, depends on Heaven, and is governed by the Dao.”

According to him, the physician’s role is primarily to prevent illnesses from arising: “Treating an illness that has already manifested is like digging a well when one is thirsty, or forging weapons after a war has begun.” (Neijing, Suwen, chap. 2). This preventative approach, still central to Traditional Chinese Medicine, reveals the pragmatic and visionary intelligence attributed to the Yellow Emperor.

Virtues and personality

Huang Di is described as a model of wisdom, temperance, and virtue. He is a sovereign who listens to his advisors, respects the laws of nature, and governs by example. He follows the path of the “golden mean”: neither excess nor deficiency, but a constant pursuit of harmony. In the Neijing, he emphasizes the importance of living in accordance with the seasons: “In spring and summer, nourish growth; in autumn and winter, protect contemplation. He who follows the path of the seasons avoids illness.”

Thus, Huang Di embodies an innate ecological awareness, based on a profound respect for the cycles of life and the interdependence between humankind and its environment. On a moral level, he is the archetype of the wise and benevolent sovereign, at the service of his people. He governs not by force, but by virtue. He is “the son of Heaven who enlightens mankind without dominating them.”

Heritage and posterity

Huang Di’s influence has endured through the ages. He remains a key figure in Chinese political, philosophical, and medical thought. His veneration continues to this day, notably in Huangling, Shaanxi Province, where annual ceremonies honor his memory.

His legacy is also reflected in the central role of health in Chinese culture. By placing prevention, balance, and natural regulation at the heart of his teachings, Huang Di inspired not only medicine but also the philosophy of daily life: diet, breathing, and energy practices such as qigong.

Huang Di thus embodies a timeless ideal: that of a sovereign who unites science, wisdom, and spirituality. He reminds us that governing, like healing, consists above all in maintaining balance and respecting the laws of life: “The wise person observes Heaven and Earth, understands the energies, and protects life.”

Thus, the figure of Huang Di continues to profoundly influence Chinese culture today. He is a symbol of the unity of the Chinese people and of ancestral wisdom. His model continues to inform contemporary Chinese medical and philosophical thought.

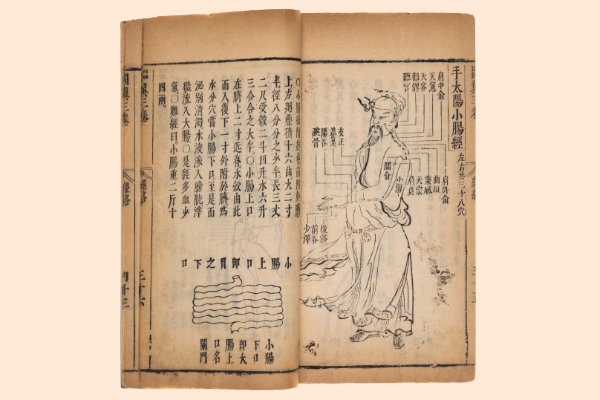

The Huangdi Neijing, a masterpiece of TCM

The Huangdi Neijing (黃帝內經, Yellow Emperor’s Inner Classic) is considered the foundational text of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Likely composed between the 3rd and 1st centuries BCE, it is divided into two main parts: the Suwen (素問, Simple Questions) and the Lingshu (靈樞, Spiritual Pivot). The Suwen addresses major medical theories: Yin-Yang, the Five Elements, Qi, the causes of disease, prevention, and dietetics. The Lingshu focuses more on practical matters, particularly acupuncture, detailing the meridians and energy points.

The dialogue format between Huangdi and his physician Qibo brings the text to life: the emperor asks pertinent, sometimes naive, questions, to which Qibo responds with clear and philosophical explanations. This pedagogical style reflects the idea that knowledge is the result of exchange, not imposition.

Among its key principles is the idea that health depends on a dynamic harmony between humankind and nature. Thus, “human beings are microcosms reflecting the macrocosm,” and their imbalances represent a disruption of natural cycles.

Even today, the Neijing serves as a reference for practitioners of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). It is not only a medical manual but also a philosophical treatise, where science, spirituality, and empirical observation converge. As a famous phrase from the Suwen emphasizes: “The wise person does not treat the disease, but rather what precedes it.”