Mindfulness

A living presence at the heart of the experience

Mindfulness is experiencing a surge in popularity today. How can we explain this phenomenon? In our Traditional Medicine practice, we are seeing more and more patients complaining of anxiety and sleep disorders. Their Shen (spirit) is troubled by an incessant stream of thoughts, their bodies are tense from chronic stress, and their Qi (vital energy) is not flowing harmoniously. And we observe, year after year, that this trend is not improving. Thus, mindfulness is not a modern fad, but a vital need, a profound response to an era where everything conspires to uproot us from the present moment.

We have seen many lives transformed when patients begin to cultivate this mindful presence. It aligns so naturally with the principles of Taoism that we have made it our daily practice: listening to our sensations and emotions, acting without forcing. Let’s explore this art of living together—simple in theory, but demanding in practice, especially when our external environment bombards us with distractions.

What is mindfulness?

What is mindfulness? Imagine this: you’re sitting, your breath is flowing, and suddenly a thought pops up: “Oh, I forgot about that appointment…” Instead of diving into it, you let it pass like a cloud in the sky. That’s mindfulness: a kind, non-judgmental attention to what is here, now—the sensation in your stomach, the warmth in your hands, the sound of rain outside…

No rigid concentration, no forced relaxation. Just an observation: “This is what is,” without judgment or analysis. In our practice, we see this quality as a form of subtle observation of the Shen (spirit) and Qi. When a patient begins to perceive their tensions without immediately trying to push them away, the Qi already flows more freely.

Deep roots in Taoism

In early Buddhism, sati (mindfulness) is the ability to observe the body, sensations, mind, and phenomena without judgment, remaining clear-headed in the face of bodily, sensory, and mental manifestations.

In Taoism, wu wei, this often misunderstood “non-action,” is not laziness. It is acting in perfect harmony with the Tao, without the intervention of the ego. To achieve this, one must first perceive the natural rhythms—the flow of Qi, openings, and blockages. We practice this subtle perception with our patients. It is this perception that allows us, in particular, to sense where Qi stagnates, where it lacks fluidity.

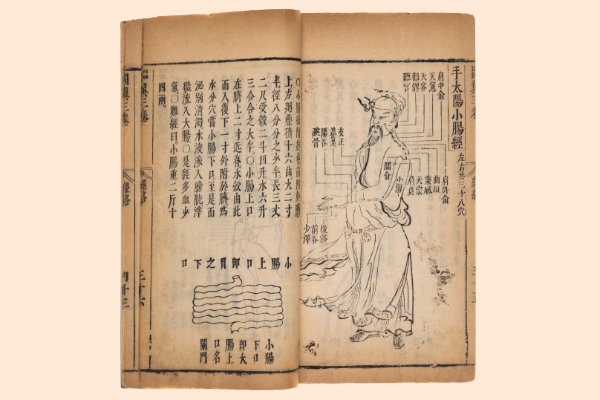

The Huangdi Neijing, the foundational text of Chinese Medicine, states it clearly: perfect health arises from harmony with the seasons, emotions, heaven, and earth. “Know thyself”—this Socratic invitation resonates with this approach to mindfulness. Indeed, this state of being open to oneself and to the present moment is a path to knowledge, even wisdom.

Training mindfulness

So, how do you practice mindfulness? As practitioners of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), in addition to our treatments, we often guide our patients toward simple practices that enhance the work done during sessions. Here are a few:

- Conscious breathing: Sit down and observe your breath as it is. This is the most reliable anchor. It calms the agitated Shen and tonifies Lung Qi.

- Body scan: Mentally scan your body, area by area. Note any tension, tingling, heaviness… without correcting it. This refines awareness of the meridians.

- Observing thoughts: Watch them like leaves carried by a river. They come, transform, and go. The less you cling to them, the less the Liver stagnates.

- Conscious movement: Slow walking, Tai Chi, or basic Qigong. Focus your attention on the contact of your feet with the ground, relaxation, the swinging of your arms, and the flow of Qi in your limbs.

Practice daily

But the real magic happens when you integrate this mindfulness into your daily life. That’s when it becomes powerful. After a few weeks, our patients report: “I cooked while being truly present… and being relaxed allowed me to be incredibly faster.”

Practice mindful eating. Look at the colors of your food, savor the aromas, taste each bite fully… Also, learn to identify hunger and satiety signals. At the same time, you’ll be contributing to the preservation of your Spleen and Stomach.

Experiment during a conversation. Truly listen to the other person—without preparing your response, without judging. Remain aware of your own breath, the warmth rising and falling within you, and any emotions that may arise. Misunderstandings diminish, relationships become more peaceful, and Liver Qi flows more freely.

The benefits of mindfulness

Numerous studies from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the American Psychological Association (APA), the Mayo Clinic, and Johns Hopkins confirm what we observe clinically: mindfulness reduces chronic stress, alleviates anxiety and rumination, and improves emotional regulation.

Two programs have been particularly effective:

- Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) by Jon Kabat-Zinn, excellent for managing chronic pain and daily stress.

- Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), highly effective in preventing depressive relapses in those who have already experienced several.

The observed effects include: improved sleep, reduced muscle tension, and a heightened awareness of bodily signals (cold, heat, fatigue, etc.). These effects are moderate but lasting—and they complement our treatments with acupuncture, Tuina massage, or traditional Chinese medicine.

Let’s be honest: mindfulness is not a miracle cure. It’s not the end of difficulties. Life remains what it is: joys, sorrows, unexpected events. But with mindfulness, we navigate them differently—with greater clarity, stability, acceptance, and therefore, gentleness toward ourselves and others.

And you? Ready to focus your attention on the present moment, day after day? The true treasure—your health, your inner peace—is already there, waiting for you to notice it.

Tell us in the comments or during a consultation: what small, mindful action will you try this week?

When inner quality shapes the act

Mindfulness is not simply about observing what is. When it is stable and embodied, it allows us to introduce a clear intention into our actions, without tension or excessive willpower. Intention is not a repetitive thought or a mental wish; it is a silent orientation of mind and heart that permeates the gesture.

In Ayurveda, it is said that cooking calmly, with attention and kindness, transforms the subtle quality of food. The same dish, prepared hastily or in a fit of anger, does not nourish in the same way. It is not the ingredient that changes, but the inner state of the person performing the action. Mindfulness makes this state perceptible and therefore adjustable.

In medical practice, this dimension is crucial. In our practice, we are fully present with our patients. Thus, we do not provide care mechanically. For example, when we insert acupuncture needles into a woman experiencing fertility difficulties, our action will be performed with full awareness. Thus, in silence, we set a clear intention: that the flow of hormones will regulate and that the patient will open herself to fertility again. This intention is not spoken aloud; it discreetly accompanies the act.

Mindfulness prevents the intention from becoming a rigid will. It keeps it flexible, attuned, and respectful of the rhythms of life.