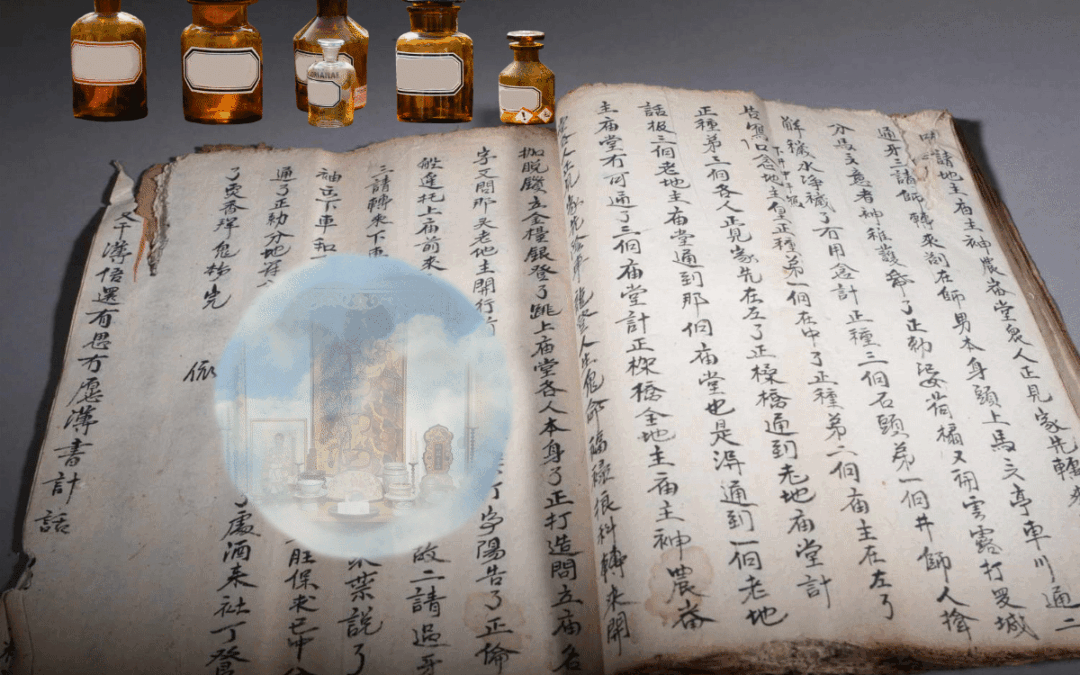

Pharmacopoeia – the recipe

The subtle art of synergy between ingredients

Chinese pharmacopoeia, a cornerstone of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), is based on a holistic approach. It aims to restore the body’s energy balance (qi, yin-yang, and the Five Elements) in the face of pathological imbalances. Unlike Western medicine, which focuses on eliminating a specific symptom, TCM treats the person as a whole. It takes into account the underlying causes, associated symptoms, and also emotional or environmental influences.

Thus, the key to this approach lies in the meticulous construction of the remedies. These combine several ingredients to address the complexity of energy imbalances.

This article is the second in a series of three. The first is devoted to the ingredients, the next to the prescription.

Recipe structure

In Chinese medicine, a recipe is much more than a simple list of ingredients. It is a strategic composition in which each substance plays a precise role. It is comparable to a team where each member has a specific task to achieve a common goal.

These roles are inspired by the Chinese imperial hierarchy, making them intuitive to understand, even for a layperson. Here are the four main roles:

The Sovereign (jūn)

The Sovereign is the main ingredient. It directly addresses the root cause of the illness. It is the “leader” of the recipe, the one who defines the primary action.

The Minister (chén)

The Minister supports the action of the Sovereign or treats secondary symptoms related to the illness. It acts as a “second” that reinforces or complements the action of the leader.

The Advisor (zuǒ)

The Advisor adjusts the energetic properties of the prescription or treats associated symptoms that are not directly related to the primary cause. He acts as a “strategist,” refining the approach.

The Ambassador (shǐ)

The ambassador harmonizes the interactions between the ingredients or guides the prescription’s action toward a specific meridian or organ. He plays the role of a “diplomat,” ensuring the overall harmony.

In Chinese medicine, a recipe is much more than a simple list of ingredients. It is a strategic composition in which each substance plays a precise role. It resembles a team where each member has a specific task to achieve a common goal.

These roles are inspired by the Chinese imperial hierarchy, which makes them easier to understand, even for a uninitiated. Here are the four main roles.

Balancing energies

A fundamental principle of Chinese medicine is maintaining energetic balance. This prevents the use of remedies from creating new imbalances.

Each substance possesses:

- an energetic nature (sì qì: cold, cool, warm, hot)

- a flavor (wǔ wèi: pungent, sweet, sour, bitter, salty)

These characteristics influence its action on the body. For example, a warming herb like Gān Jiāng (dried ginger) warms the Stomach. However, if used alone in excess, it can cause excessive heat and symptoms such as thirst or irritability.

To avoid this, secondary remedies—ministers, advisors, and ambassadors—adjust the properties of the sovereign.

For example, a warming herb like Gān Jiāng (dried ginger) can be combined with a cooling herb like Huáng Lián (Chinese filodendron) to balance the thermal effects.

In a prescription for abdominal pain due to internal cold, Gān Jiāng warms, but Huáng Lián can be added in small quantities to prevent overheating, which would worsen the patient’s condition.

Another example is in Bái Hǔ Tāng – White Tiger Decoction, used to treat high fevers due to excessive heat in the body:

Shí Gāo (gypsum) is the sovereign, with a very cold nature that eliminates intense heat. However, this coldness could damage the Stomach, which prefers a gentler energy.

To balance the ingredients, Gān Cǎo (licorice) and Gěng Mǐ (rice) are added as adjuvants. These gentle ingredients protect the stomach and soften the harsh effect of Shí Gāo.

In the box below, we will explain the recipe for the Ephedra decoction in detail.

Synergies and incompatibilities

Synergies (xiāng xū) are at the heart of the effectiveness of Chinese remedies. They occur when several substances work together to amplify their effects.

For example, in Sì Jūn Zǐ Tāng – Four Gentlemen’s Decoction – Rén Shēn (Panax ginseng) and Bái Zhú (Atractylodes macrocephala) work synergistically to tonify the Spleen’s qi. They strengthen vital energy and improve digestion. Together, they are more effective than when used separately.

Conversely, certain combinations should be avoided. The “Eighteen Incompatible Herbs” (shí bā fǎn) can be ineffective or toxic. Similarly, the “Nineteen Fears” (shí jiǔ wèi) indicate pairs to be used with caution.

In cooking, some flavors go well together – like lemon and honey – while others create an unpleasant mixture – like vinegar and milk. In medicine, these combinations are avoided to protect the patient.

Thus, Chinese medicine is never limited to the use of a single plant, just as it does not treat the body independently of the mind. Each remedy is a complex composition in which several substances work together to restore the patient’s overall harmony.

The roles of sovereign, minister, advisor, and ambassador ensure that imbalances are addressed in a multidimensional way, taking into account energetic interactions and the specific characteristics of each individual. This mind-body approach, rooted in millennia of practice, illustrates the richness and depth of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), where health is a dynamic balance between the individual and their environment.

The Má Huáng Tāng recipe (Ephedra Decoction)

Ma Huang Tang – or Ephedra Decoction – is one of the oldest and most powerful remedies in classical Chinese medicine. It is used to treat a cold with chills but no sweating.

1. Ma Huang (Ephedra) is the sovereign. This plant works by dispersing wind-cold (an external pathogenic factor) and inducing sweating to clear the body’s surface (biǎo).

In simple terms, imagine Ma Huang as the general who gives the main order to fight the enemy (wind-cold).

2. Guì Zhi (Cinnamon Branch) is the minister. It warms the meridians (energy channels) and mobilizes qi to amplify the effect of Ma Huang.

Here, we should see the minister as an assistant who helps the general execute his plan while managing other aspects of the battle.

3. Xìng Rén (Bitter Almond) is the advisor who helps lower pulmonary qi, thus relieving the cough or chest tightness often associated with a cold.

The image is that of an expert who offers solutions for secondary problems, such as calming a cough while fighting the cold.

4. Gān Cǎo (Licorice) is the ambassador; it harmonizes the effects of other herbs and reduces the risk of side effects.

The ambassador is like a coordinator who ensures the team works together without conflict.

Simple explanation of the recipe

Imagine you have a cold with chills, but you’re not sweating, and you have a slight cough. Má Huáng (the sovereign) acts like a medicine that makes you sweat to expel the cold. Guì Zhī (the minister) adds warmth to support this process. Xìng Rén (the advisor) takes care of the cough so you can breathe more easily. Finally, Gān Cǎo (the ambassador) ensures that all these herbs work together without irritating your stomach or causing other discomfort.