The art of the unique prescription

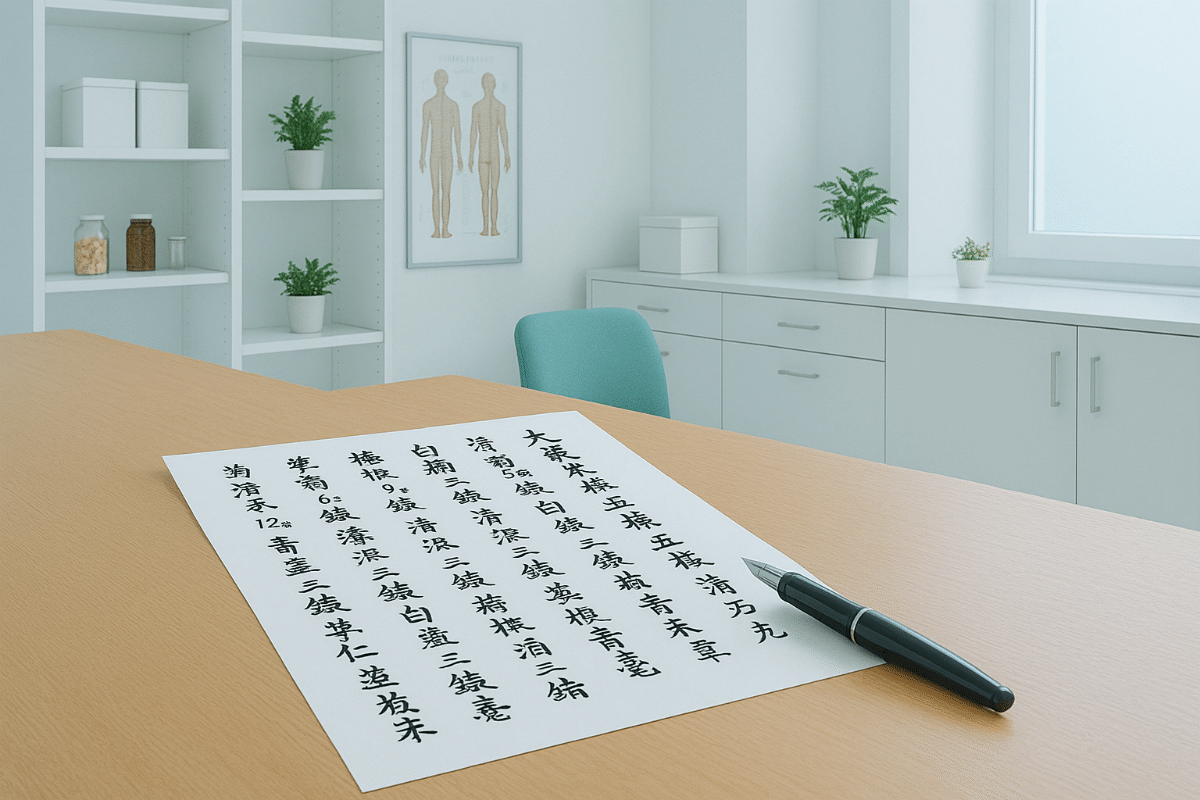

In this third article dedicated to Chinese medicine, we discuss the prescription. Unlike Western medicine, TCM offers personalized prescriptions, tailored to each individual.

Therefore, there are no standard treatments! Each prescription is crafted like a work of art, adapted to each person’s unique energy profile. It takes into account the specific energetic diagnosis for that patient at that moment. The practitioner may use a classic recipe as is, or modify it (change the doses, add/remove certain herbs) according to the patient’s unique symptoms.

As explained in our previous article on the recipe, Chinese medicine combines several ingredients to optimize their effectiveness while targeting specific imbalances. Whether you suffer from fatigue, stress, or pain, your prescription will be as unique as your fingerprint.

Discover how these remedies, rooted in millennia-old wisdom, restore harmony to the body and mind.

Eight forms of absorption

As with Western medicines, Chinese remedies take different forms depending on the needs and always with the goal of maximum effectiveness. Here are eight commonly used techniques for consuming remedies in the Chinese pharmacopoeia, based on traditional practices:

Decoction (煎剂, Jiānjì):

The most common method, consisting of boiling herbs in water to extract their active ingredients. The decoction is drunk hot or warm, often in several doses.

Infusion (泡剂, Pàojì):

Herbs are infused in hot water, without prolonged boiling, to preserve volatile compounds. Used for delicate or aromatic herbs.

Powder (散剂, Sǎnjì):

The herbs are ground into a fine powder and consumed directly. This form allows for rapid administration and easy storage. It offers a practical compromise. Slower to act than decoctions but faster than tablets, it is suitable for moderate treatments.

Pills or granules (丸剂, Wánjì):

The herbs are processed into small pills or granules, often bound with honey, flour, or other excipients. Convenient for prolonged use or easy administration.

Paste or jelly (膏剂, Gāojì):

A concentrated preparation obtained by reducing a decoction, often mixed with honey or sugar. Used for long-term treatments, particularly for tonic purposes.

Tincture or maceration (酊剂, Dǐngjì):

Herbs are macerated in alcohol or another solvent to extract their active ingredients. This method is used for specific treatments or for long-term preservation.

External application (外用, Wàiyòng):

Herbs are applied to the skin as poultices, ointments, or compresses to treat local pain, inflammation, or injuries.

Inhalation (熏剂, Xūnjì):

Herbs are burned or heated to produce inhaled vapors, often to treat respiratory problems or for calming effects.

These techniques are chosen according to the condition, the patient’s constitution, and the properties of the herbs.

The seven main categories

The Chinese pharmacopoeia contains over 100,000 remedies, which are classified into seven categories. These categories take into account their therapeutic purpose and complexity. Imagine your health as a river. Depending on the obstacles encountered, the doctor will choose the appropriate “hydraulic force,” in other words, they will prescribe according to the severity of the condition. Here are these seven categories.

Major Ordinance (dà fāng)

It is used for complex conditions requiring numerous ingredients (often 10 or more). For example, a prescription for a chronic illness with multiple imbalances (fatigue, pain, digestive issues) might include tonics, dispersants, and harmonizers. It’s like a large orchestra where each musician plays a key role.

Minor Ordinance (xiǎo fāng)

Simpler, with fewer ingredients (4 to 6), the minor prescription targets specific symptoms. For example, the Yín Qiào Sǎn recipe treats sore throats and fever associated with a cold. It’s like a small team focused on a specific task.

Prescriptions According to Rhythm

Slow Prescription (huǎn fāng)

Designed for chronic illnesses, the slow prescription works gradually to strengthen the body without shocking it. For example, Bǔ Zhōng Yì Qì Tāng treats chronic fatigue by tonifying qi over the long term. Think of a gardener who regularly waters a plant to help it grow.

Rapid Prescription (jifang)

The rapid prescription is used for acute conditions, such as a sudden fever. Thus, Huang Lian Jiě Du Tang combines Huang Lian (Coptis chinensis), Huang Qín (Scutellaria baicalensis), Huang Bai (Phellodendron amurense), and Zhi Zi (Gardenia jasminoides) to disperse the fire in the Triple Burner. This is indicated for high fevers and restlessness. It is like a fire extinguisher that acts quickly to put out a fire.

Prescriptions according to complexity

Odd prescription (qí fāng)

An odd-numbered prescription is designed for a single etiology (cause). For example, a prescription for a wind-cold cough might focus solely on dispersing that pathogen. It’s like a sniper targeting a single target.

Even prescription (ǒu fāng)

The paired ordinance combines two sovereigns to treat two simultaneous causes. For example, an ordinance for blood stagnation and qi weakness might include Tao Ren (for blood) and Huang Qi (for qi). It’s like two leaders working together to solve two problems at the same time.

Complex ordering (fù fāng)

Complex prescriptions address multifactorial conditions with multiple causes and symptoms. For example, a prescription for a patient with chronic pain, insomnia, and digestive weakness might include herbs to calm the mind, tonify the spleen, and relieve pain. It’s like a puzzle where each piece fits together to form a complete picture.

Twenty-two families of prescriptions

In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), remedies are also classified into 22 categories according to their primary action. Here are the most common:

Tonic

Strengthen energy (qi, blood, yin, yang) for those who are tired or recovering from illness.

Biao Releasers

Repel external aggressions such as colds.

Harmonizers

Rebalance the organs to soothe stress or emotional disturbances.

Qi Regulators

Unblock energy to relieve tension and pain.

Blood Regulators

Improve circulation to treat painful periods or hematomas.

Emetics and Purgatives

Eliminate toxins in cases of poisoning or severe constipation.

Dispersants

Expel the “six climatic pathogens” (wind, cold, heat, dampness, dryness, and extreme heat).

Transforming

Clear mucus or food stagnation.

Astringent

Control excessive sweating, diarrhea, or bleeding.

Specialized

Target specific needs (vision, parasites, gynecology, emergencies).

Thus, each type of prescription is like a different tool in a toolbox. A hammer is perfect for driving a nail quickly, but to build a complex house you need a wide range of specific and complementary tools.

Each prescription is a complex composition where several substances work synergistically to restore the patient’s overall harmony, as detailed in “Pharmacopoeia – The Recipe.”

This mind-body approach, rooted in millennia of practice, illustrates the richness and depth of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), where health results from a dynamic balance between the individual and their environment.

Key takeaways

Your prescription reflects a personalized energetic diagnosis. Its form (decoction, tablets, etc.) optimizes absorption according to your constitution and lifestyle. Its classification (major/minor, rapid/slow, etc.) reveals the chosen therapeutic strategy.

Signs of a suitable prescription:

- Progressive improvement in sleep and energy

- Regulation of bodily functions (digestion, bowel movements, cycles)

- Reduction of symptoms without bothersome side effects

- Overall feeling of well-being

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) does not treat a disease but rebalances the individual. Your prescription is therefore unique, like your energetic fingerprint. It will evolve with you, becoming more refined over the course of consultations to perfectly match your current needs.

In summary, the structure of prescriptions in Traditional Chinese Medicine is a methodical and balanced approach that reflects the holistic vision of TCM.

0 Comments